As I write this my hands are covered in oil and grime. Nikki still has some oil on her face making her look more like a coal miner than a sailor. We hardly notice after everything else we have been though.

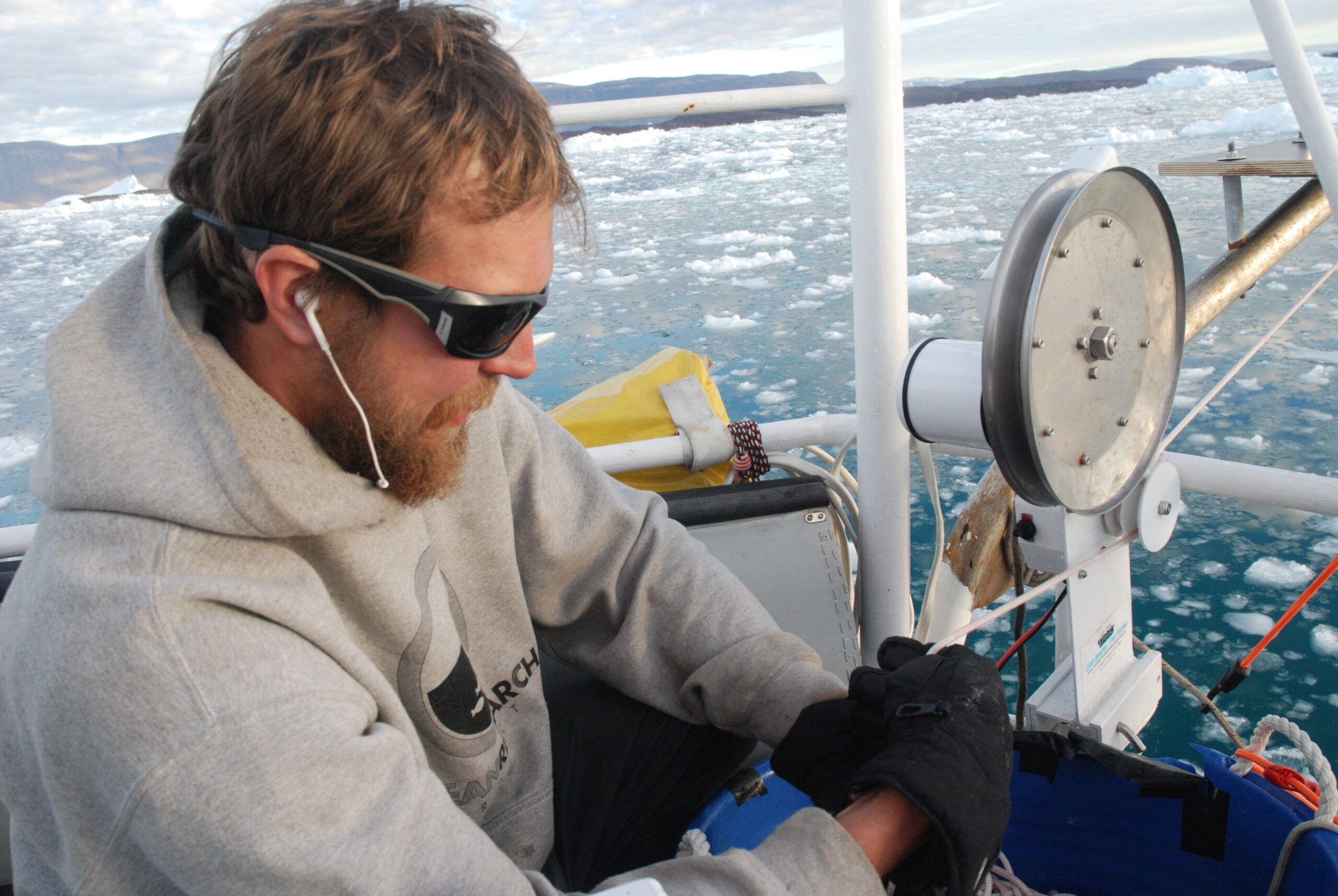

Since my last blog we had a good weather window and spent 10 days straight working around the clock surveying Inglefield fjord for NASA’s OMG program. We were running out of time and we desperately needed a long spell of good weather to complete our survey. Especially in areas of heavy ice where you can only enter if it’s flat calm.

Considering all the bad weather and issues with our scientific equipment, we did a good job completing the survey. It was a lot of work and it will provide NASA with important information about how ocean currents influence climate change that region of Northwest Greenland.

Etah or bust has been our motto since the boatyard in Sisimiut. Etah is a fjord in the far north of Greenland roughly 700 miles from the North Pole that was used by various explorers during the great age of exploration. It’s a beautiful area, very green, which is abnormal that far north.

Going to Etah was the prize for completing the survey on time. If we didn’t complete the survey or if we didn’t get it done early enough we wouldn’t go. “Etah or Bust” was our rally cry, our motivation; it’s what we all looked forward to.

Etah is only 80 miles north of Qaanaaq and Inglefield fjord so it wasn’t that much further north than we already were. It only took us 24 hours to get there. Unfortunately our timing coincided with an adventure tourist cruise ship. I hate adventure tourism.

Imagine you were climbing a tall remote mountain and for two months you worked hard to reach the summit. You dealt with hunger, sleep deprivation and daily hardships. Finally the day you reach the top of the mountain as you climb the last crest you see a luxurious mega passenger helicopter sitting on the summit (mega passenger helicopters don’t exist so bear with me, it’s just an analogy). You see around this helicopter (cruise ship) hundreds of adventure tourists all dressed in spotless matching red jackets with clean pressed pants walking around taking pictures of anything and everything. You on the other hand haven’t had a decent shower in two months; your clothes are dirty, your hair is a mess and you haven’t shaven in weeks. As you get closer to the summit the happy adventure tourists notice you and start taking pictures of you like you’re some kind of mountain Neanderthal. They approach you in groups asking silly questions like, “where do you do laundry?”, “how do you go to the bathroom”? The glorious moment you have pictured in your mind for the last two months, summiting the mountain, has been completely dashed to pieces. You slump down on a rock trying to get away from the hundreds of adventure tourists who are sharing the summit with you, but they are everywhere. You overhear one of them, an older woman with big diamond earrings tell a man in perfectly pressed slacks, “we must be getting back on board, we don’t want to miss our champagne dinner” and the happy tourists start boarding the mega helicopter. In a whirlwind dust and noise the helicopter takes off. You sit there for a moment trying to find the glorious victory you had imagined for the last two months but the moment has been ruined. You feel your stomach growl, time for another freeze dried meal and two more months of hiking back down the mountain.

That’s what it’s like to come across a group of adventure tourists at the ends of the earth.

We were only in Etah for 24 hours before heading back south to Qaanaaq. We only stayed in Qaanaaq long enough to get the fuel, food and water we would need for our push south back down to Upernavik some 350 miles away. We were in a hurry because there was another gale coming and we wanted to get to a protected area and drop anchor before the strong winds came. When paying for the fuel I looked over a Danish weather forecast with the manager of the fuel depot. It didn’t look that bad, he said “not much wind just rain”. I figured it would be a gale but nothing worse, so off we went to drop anchor.

The winds picked up through the night and by morning they were a good 50kts. We were anchored in a good location and the anchor was holding so all seemed ok. This was our fourth storm on anchor and we were used to the situation. You could say I was caught with my pants down as I was on the toilet when I heard Nikki yell “the anchor is dragging”!

This has happened before so at first it didn’t seem to be a big deal. Then the winds quickly increased to hurricane strength and the anchor line snapped twenty feet down from the bow. Things were changing for the worse very quickly.

The winds and rain were so strong that we were in white out conditions, much like a blizzard. The winds were pushing the boat over so far that water was pouring into our pilot house. Then we felt a strong bang. As luck had it we had found a group of uncharted rocks and we were now banging up against them. We were healed so far over and the waves were large enough that we were able to bounce our way over the rocks. Once over the rocks I decided we should deploy the parachute sea. Before we could get it deployed we must have drifted over an unmarked shoal because a large wave hit us knocking the boat down and putting its masts in the water.

Once the parachute sea anchor (Para anchor) was deployed our boat slowed down and put its bow back up into the wind and waves. For a moment things were much better. I still had to use the engine to slowly push the boat and Para anchor one direction or another to avoid large icebergs. Problem is icebergs don’t drift at the same rate as you do on a parachute sea anchor, you could drift right down on one.

There was some excess line that didn’t get deployed properly when the Para anchor was deployed. I had to stay at the helm during the deployment so I didn’t see what happened to it. Twenty minutes later I looked down and I see a line under our boat. I yelled to the mate “there is a line under our boat, we need to bring it up right now or it could wrap around the propeller”! The winds we too strong to just walk up to the bow, you would have put on a harness and tether and crawl on your hands and knees with icy waves crashing over your head. My Mate had reached his limit, I couldn’t get him to go outside and bring in the line. I would have done it myself but I was trying to maneuver the boat slowly between some uncharted rocks and an iceberg. A few minutes later what I feared would happen happened, the line wrapped in our prop and the engine died. Our situation went from bad yet under control to downright dangerous. I decided then to make a distress call.

The Danish Navy keeps a boat at Thule air base about 100 miles from Qaanaaq. Their boats are fast enough that it only takes them 6 hours to cover that distance. While we were waiting for the navy ship to arrive we put on immersion suits and prepared the life raft. The winds were still blowing hurricane force and we were getting knocked around quite a bit. Alexander and Dana were both puking, the floor of the boat was covered with random stuff and everything was wet. The biggest threat was that we would be slowly pushed into an iceberg; the boat would be dashed upon it like a cliff in a storm. With the Para anchor in place the waves and wind were no longer a threat but icebergs were a different story. We passed by one just a few hundred feet away. It was still white out conditions, hard to see an iceberg, even our radar was struggling. We still had one more trick up our sleeves, if we had to I could cut the Para anchor free and we could out maneuver an iceberg under minimal sail. That would also have been bad as we would have no good way to stabilize Ault against the unrelenting wind and seas, but it’s better than being dashed up against an iceberg.

The Danish Navy arrived before we drifted near another iceberg. As they arrived the winds started to ease up. They tossed us a tow line and proceeded to tow us behind an island to get protection from the waves. The next day they helped us cut the lines off the propeller and gave us a hot meal on their ship. They also let us borrow an additional anchor to couple with our spare anchor which we will leave for them in Upernavik, where we can buy another spare. The Danish Naval officers and crew were all very friendly and helpful.

Once we were all sorted out we dropped anchor behind an island as another storm was coming. This storm only blew 40-50kts. We drug anchor a good half mile but there was no emergency.

We had a good weather window to go south and we were all ready to get the hell out of northern Greenland and back down where the storms are not nearly as bad. The engine sounded fine at first but then the RPM’s became erratic. We limped our way into a cove surrounded by icebergs and strong currents. Before we left this year I bought a spare injector pump for our engine. It cost $1,500 which was a hard pill to swallow for a spare but I was glad I did it. It took twelve hours to replace the injector pump while on anchor in the middle of nowhere. I’ve become a good enough mechanic that I was able to do the job although I lost a very important specialized injector screw and for two hours we searched for it and all got covered with oil. Alexander was the one who found it, by then we thought we would never find it.

As I write this we are underway heading south. The engine is running well, hopefully it remains that way. I have a lot of spare parts and the skills to replace and repair many aspects of the engine but I hope I don’t have to work on it again.

We look forward to reaching Upernavik and tying off to a seawall for the first time in nearly two months.

Fortitudine Vincinimus.

Matt Rutherford